H. Sliding Blocks

Kevin Zhu

Kevin ZhuProblem Source: 2018 Asia Singapore ICPC Regionals

We are given that the blocks in the target board form a tree, so naturally it makes the most sense to root it at the one block that is already on the board at the start. Hence, it is also quite clear to see that for a given block \(b_i\), all of it’s ancestors must be placed first before \(b_i\) itself can be placed. Not only that, the block that \(b_i\) will hit when it is slid in must be the parent of \(b_i\) in the tree. Hence, by doing a simple DFS of the tree, we can easily find the direction and column or row that each block must have used to reach it’s target position. Let’s call this direction the block’s ‘slide direction’, or simply, the block’s direction. Now all that’s left for us to do is account for the ordering.

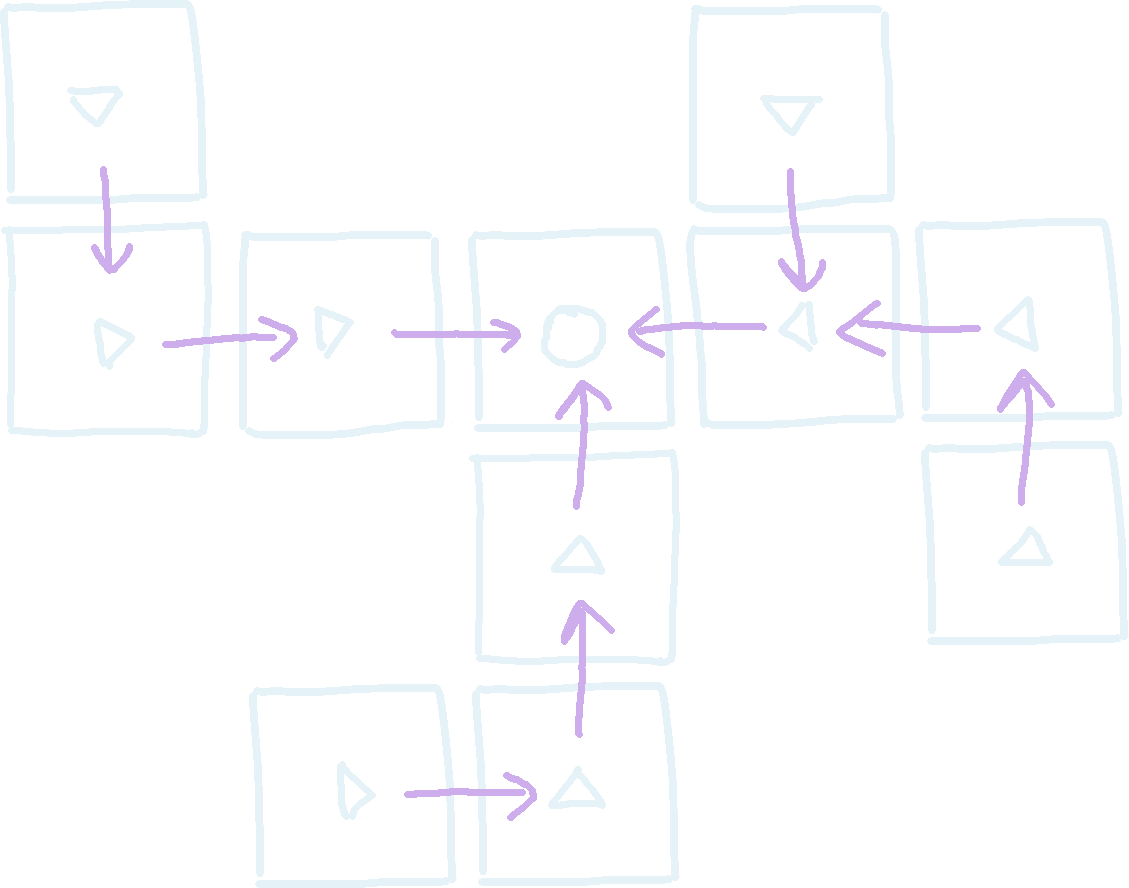

Let’s suppose block \(b_i\) is slid in from the left. Then every single other block in the target board to the left of \(b_i\)’s final position must have been placed after \(b_i\) was put into position. We can represent this ordering as a directed graph. Block \(b_i\) points to block \(b_j\) if block \(b_i\) must be placed after \(b_j\). Thus if there is a cycle in the graph, then the target board is impossible, and if there is no cycle, then we can find the ordering of the blocks using a topological sort.

Now we aim to generate the graph \(G\), by creating edges between blocks to indicate their ordering. We can begin by adding the edges implied by the tree structure, which we call ‘tree edges’.

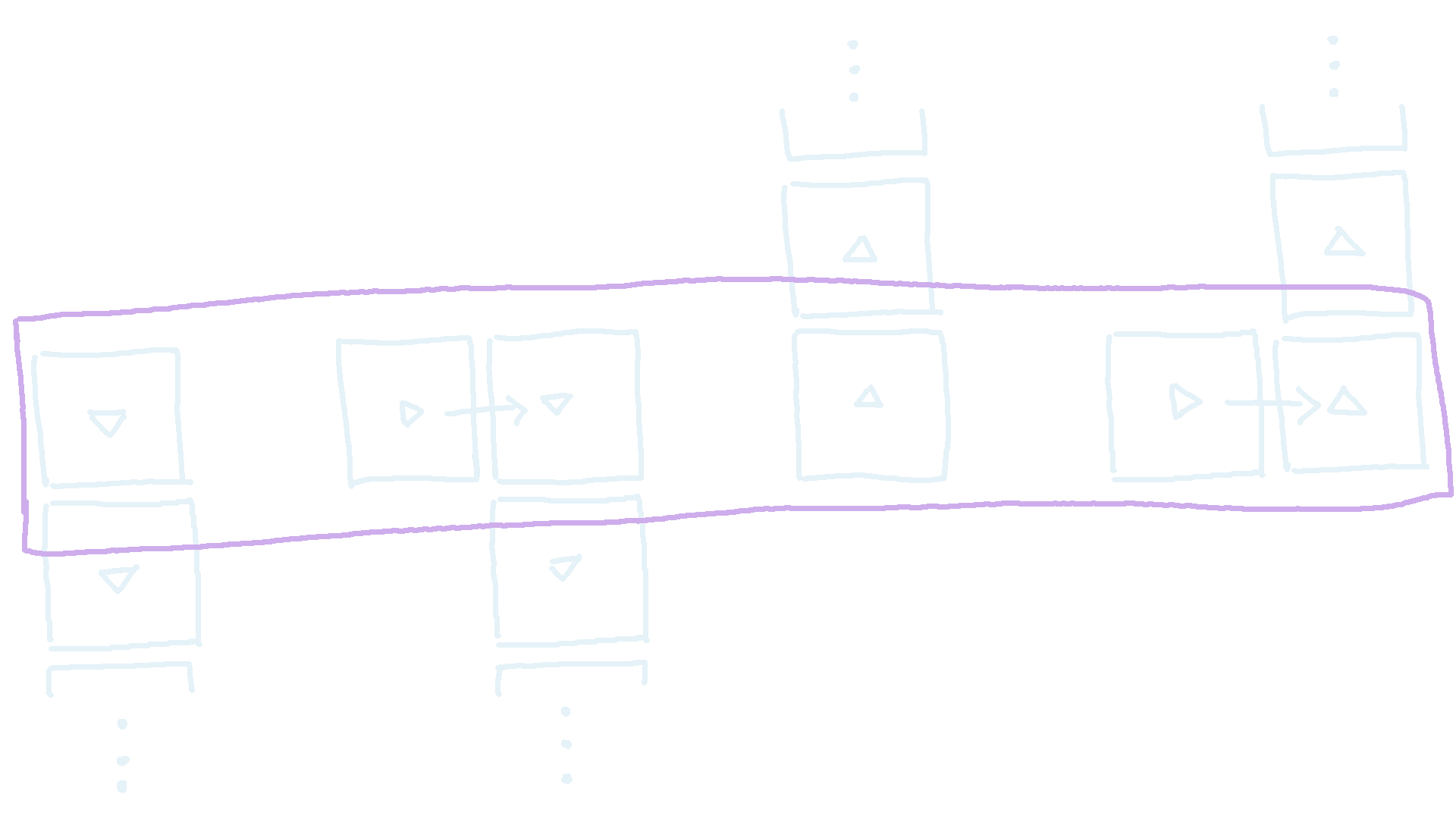

Now we have to add the rest of the edges in. For now, let’s consider only blocks that need to slide right to get to their destination. The other \(3\) directions will follow a similar process. To handle those, we loop over each row looking for blocks that have to slide right.

For each of those blocks \(b_i\), we draw an edge in \(G\) from every other block to the left of \(b_i\) pointing towards that block \(b_i\). We call these edges ‘back edges’. However, notice that this can generate an execessive number of back edges, up to \(O(B^2)\).

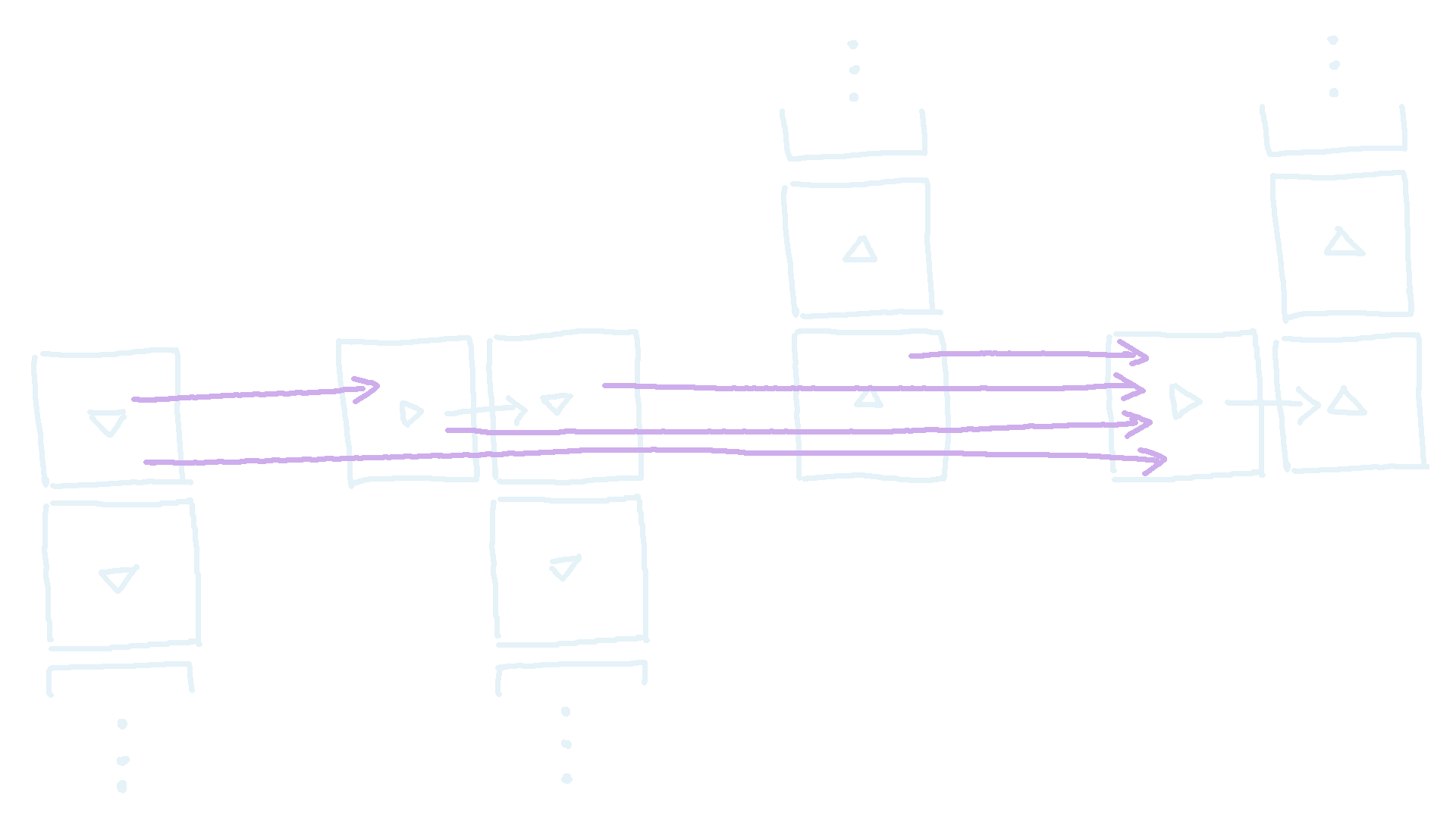

Hence we use the property of transitivity. I.e. if \(b_i\) points to \(b_j\) and \(b_j\) points to \(b_k\), then the fact that \(b_i\) points to \(b_k\) can be implied implicitly, and does not actually need to be stored. Hence, when looping backwards from block \(b_i\), we can stop at the next block that points to the right \(b_j\). We know that anything that we connect to block \(b_j\) will now implicitly point to block \(b_i\). This means that only need to generate at most one back edge per block. If we factor in all \(3\) other directions, the number of additional back edges added is a managable \(O(B)\). Once both the tree and back edges have been generated, we can run cycle detection and topological sort to get our final answer.

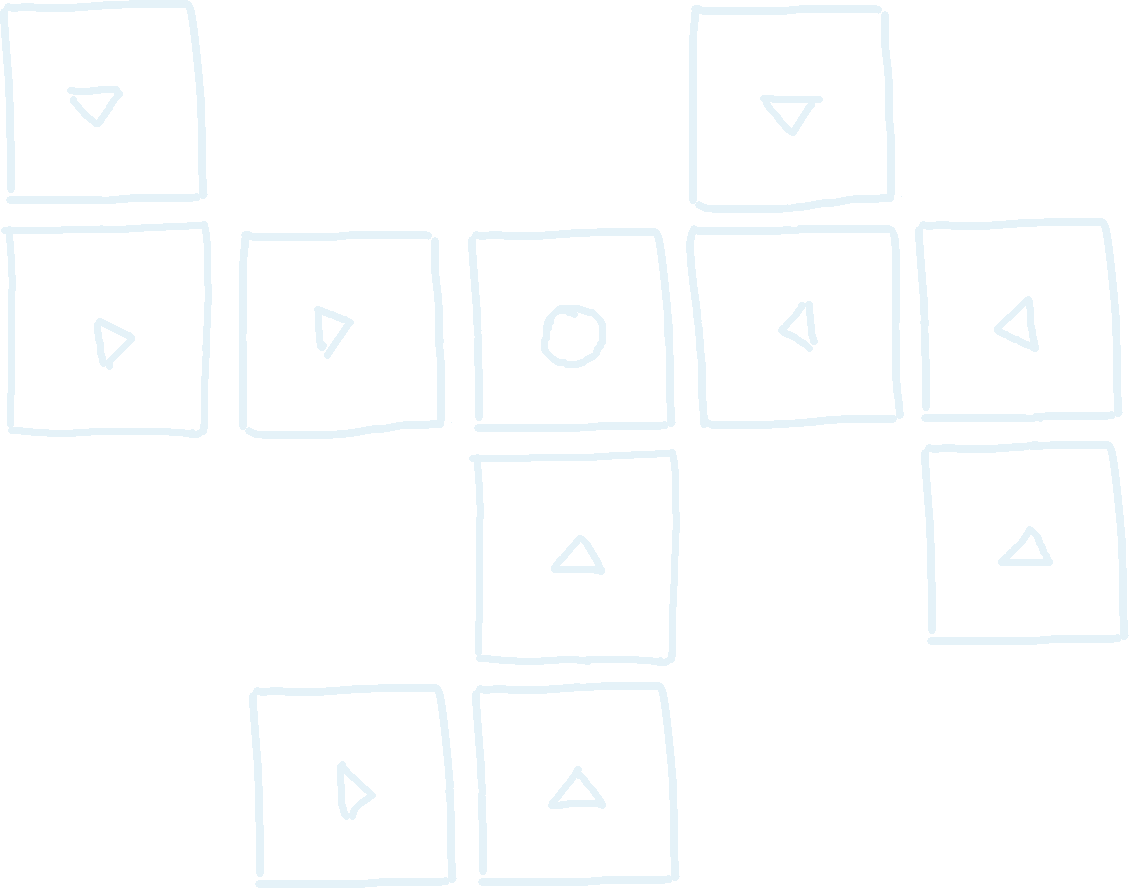

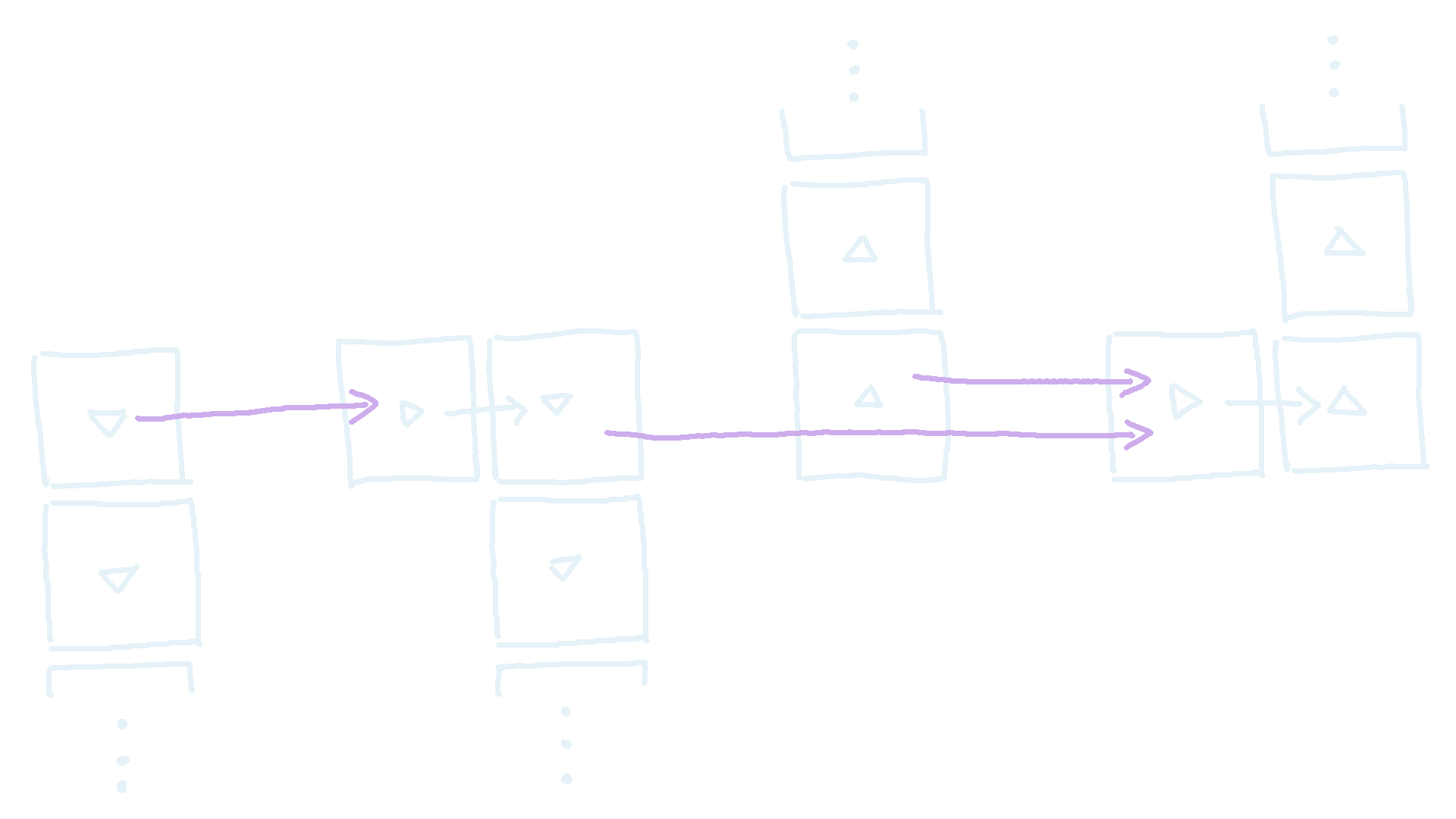

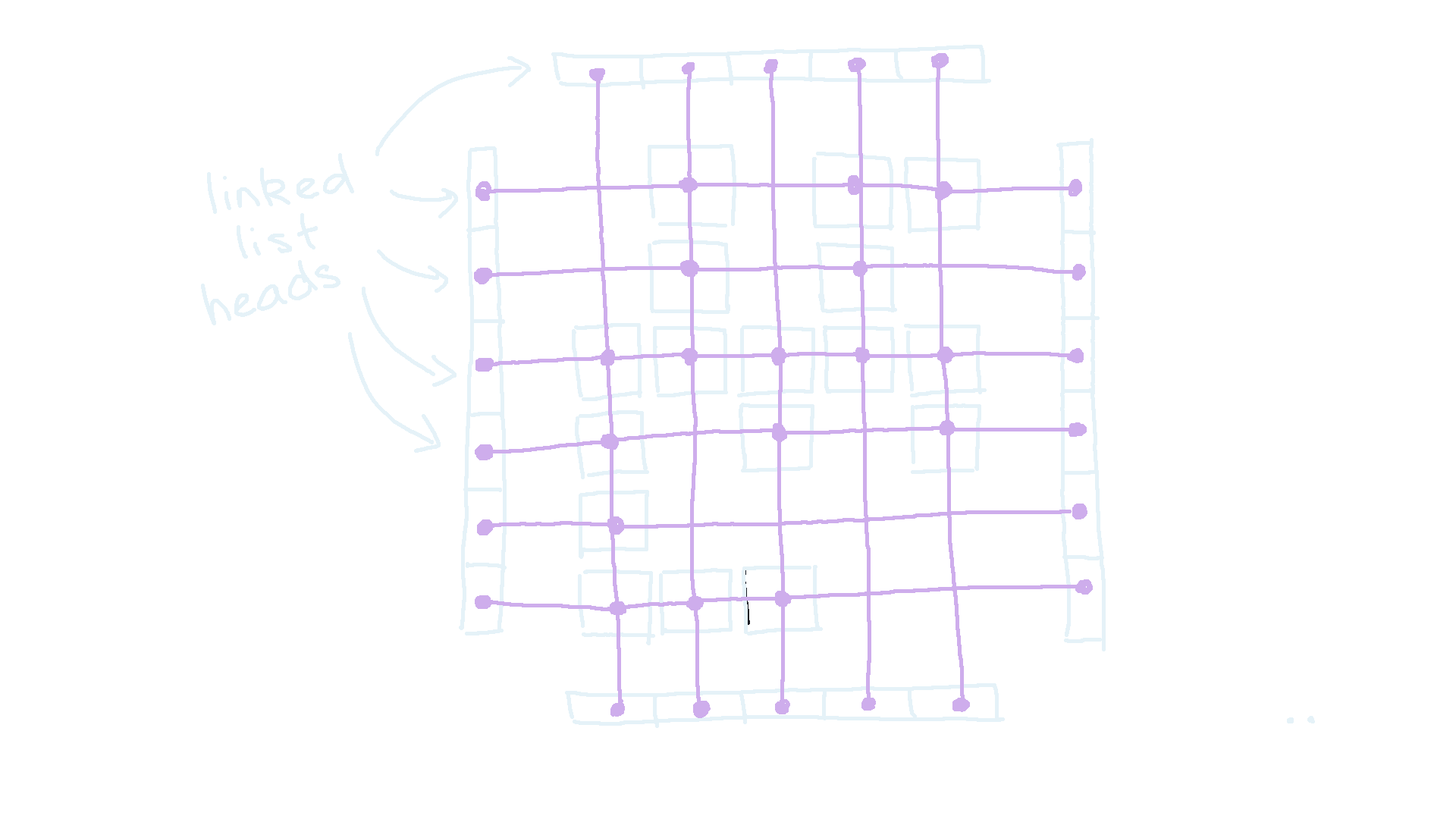

Now, let’s address how we will store our blocks. Ideally, we would like a way such that for every block \(b_i\), we can find the next block above, below, to the left, and to the right of it in constant time, since that will ensure looping through rows takes amortised \(O(B+N+M)\) instead of \(O(NM)\). There are several ways to do this, but one way is to generate a ‘linked grid’ which we call L. A linked grid stores a separate doubly linked list for each row and each column. Each linked list contains the blocks in that row or column, so that each block exists in exactly one row linked list, and one column linked list. In order to generate L, we sort the block positions by \(x\) position first, then \(y\) position. That way, if we insert the blocks in order, every insertion will be at the end of it’s respective column and row linked list, so that insertion of a single block has complexity \(O(1)\). By the end of it, every block should store a pointer to the block up, down, left, and right of it. The finished structure should look something like this:

Then, looping through the rows is as simple as going to the next block in that direction. For the DFS, when we want to find neighbouring blocks, we can simply use the manhattan distance to double check that the block is actually adjacent, and that there is no gap in between.

Now let’s look at the final complexity. Sorting the blocks is \(O(B\log B)\). Inserting them into the linked grid is \(O(B)\). Running the DFS to evaluate the slide direction and row/column number of each block as well as finding tree edges into our graph \(G\) is \(O(B)\). Looping over each row and column to to add the back edges is amortised \(O(B + N + M)\). The final graph \(G\) has \(B\) nodes and \(O(B)\) edges, so checking for cycles and generating the postfix order should take \(O(B)\). This gives us the final overall complexity of \(O(B\log B)\).

C++

#include <bits/stdc++.h>

using namespace std;

typedef long long ll;

typedef pair<int, int> pii;

typedef vector<int> vi;

#define x first

#define y second

#define pb push_back

#define all(x) x.begin(), x.end()

#define MAXN 400005

#define MAXB 400005

// each direction is associated with a number.

#define LEFT 0

#define RIGHT 1

#define UP 2

#define DOWN 3

const string dir2char = "<>^vo";

int N, M, B;

vector<pii> blocks;

struct LinkedGrid {

int start[MAXN][4]; // heads of linked list in each direction

int succ[MAXB][4]; // id of next node in each direction

LinkedGrid() {

// initialise linked list to be empty

for (int i = 0; i < MAXN; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++) {

start[i][j] = -1;

}

}

}

// function to insert an element into a row OR COLUMN

void insertrow(int i, int y, int dir) {

int l = dir;

int r = dir^1;

// if row is empty

if (start[y][r] == -1) {

start[y][r] = i;

succ[i][l] = -1;

start[y][l] = i;

succ[i][r] = -1;

return;

}

// otherwise, row contains something

succ[i][l] = start[y][l];

succ[start[y][l]][r] = i;

start[y][l] = i;

succ[i][r] = -1;

}

// insert an element into the linked list, both vertically and horizontally

void insert(int i) {

pii block = blocks[i];

insertrow(i, block.y, 0);

insertrow(i, block.x, 2);

}

// returns a row or col as a vector.

vector<int> getrow(int y, int dir) {

vector<int> ret;

int curr = start[y][dir];

while (curr != -1) {

ret.pb(curr);

curr = succ[curr][dir];

}

return ret;

}

} L;

// returns manhattan distance

int mandist(int i, int j) {

pii a = blocks[i];

pii b = blocks[j];

return abs(a.y - b.y) + abs(a.x - b.x);

}

// dfs to add tree edges and find slide directions

bool seen[MAXB];

int slidedir[MAXB];

vector<int> G[MAXB];

void dfs1(int at) {

if (seen[at]) return;

seen[at] = true;

for (int dir = 0; dir < 4; dir++) {

int to = L.succ[at][dir];

if (to == -1) continue;

if (seen[to]) continue;

if (mandist(at, to) > 1) continue;

slidedir[to] = dir^1; // store slide direction

G[to].pb(at); // add edge in graph

dfs1(to);

}

}

// check for cycles

bool act[MAXB];

bool dfs2(int at) {

if (seen[at]) return false;

seen[at] = true;

act[at] = true;

bool cycle = false;

for (int to : G[at]) {

if (act[to]) return true;

if (seen[to]) continue;

cycle |= dfs2(to);

if (cycle) break;

}

act[at] = false;

return cycle;

}

// find topological ordering

vector<int> order;

void dfs3(int at) {

if (seen[at]) return;

seen[at] = true;

for (int to : G[at]) dfs3(to);

order.pb(at);

}

int main () {

ios_base::sync_with_stdio(0); cin.tie(0);

cin >> N >> M >> B;

blocks.resize(B);

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) {

cin >> blocks[i].y >> blocks[i].x;

blocks[i].y--; blocks[i].x--;

}

pii rootblock = blocks[0];

// insert blocks into linked grid

sort(all(blocks));

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) L.insert(i);

int root = -1;

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) if (blocks[i] == rootblock) root = i;

// work out directions and tree edges

slidedir[0] = 4;

dfs1(root);

// work out back edges

for (int dir = 0; dir < 4; dir++) {

for (int y = 0; y < MAXN; y++) {

vector<int> row = L.getrow(y, dir);

int last = -1;

for (int i : row) {

if (slidedir[i] == (dir^1)) last = i;

else if (last != -1) G[i].pb(last);

}

}

}

// check for cycles

fill(seen, seen+MAXB, false);

fill(act, act+MAXB, false);

bool cycle;

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) cycle |= dfs2(i);

if (cycle) {

printf("impossible\n");

return 0;

}

// otherwise, we have a DAG. Now we get the topological order.

fill(seen, seen+MAXB, false);

for (int i = 0; i < B; i++) dfs3(i);

printf("possible\n");

for (int i : order) {

if (i == root) continue;

int y = slidedir[i] < 2 ? blocks[i].y+1 : blocks[i].x+1;

printf("%c %d\n", dir2char[slidedir[i]], y);

}

}_A neat trick that we use is choosing

LEFT = 0andRIGHT = 1. This way, ifdiris either left or right, then we can usedir ^ 1to mean the opposite direction. The same goes for up and down.

Defining

const string dir2char = "<>^vo";is a nice way of making sure you don’t have to write four if statements to print out the correct character for every direction.

More of a personal choice, but when I’m writing functions that need to work for rows and columns, I like to only think of it in terms of one or the other, never both in general. For me, it becomes easier to think about if you’re only focusing on just rows instead of trying generalise it to work for both rows and columns. This is why in my

LinkedGridstruct, my function name isinsertrow, which takes in a y coordinateyfor the height of the row, and uses the variableslandrto mean going left and right along that row. The function should work the same even if I pass in an x-coordinate intoyand pass in up or down directions into thedirargument.