Tutor CTF: Executable text file

Kevin Zhu

Kevin ZhuContest Source: COMP6[84]41 CTF

Note that all flags have been replaced with “COMP6841{REDACTED}”. This is to discourage you from just blindly submitting the final answer, and to encourage you to follow along and learn something along the way.

Exploration

We are given a file.bin which contains the following text:

UEsDBBQAAAAIAIFucFJPRmNqrwIAAKgiAAAFABwAaW50cm9VVAkAA1EdUGBRHVBgdXgLAAEE6AMA

AAToAwAA7ZpLaxNRFMfPpKmJ9pGhVKjaSMToWDWTpGh9oDY1HXMFLViJIAgxNVNbyKMkk1qLINgi

DkHoJ3Dlwk8gJQsNumhWWnfudFMIKNhFF1lY4r2dO00yUnyBujg/uDn3nPv/z31kNdy5r1y6YBME

MLHBOWDZUTG0kYd4/ZlnU0JrJ8FBf530l2nt0EioKfbaoCmCaATma23Igc9nxnVeNmOjb2M+cz2e

UFMc5mUzmj47b2W+1bIQaooBLjejE5p9Ve6rcr0ZvVznbdAzrq5oid+Z7wr1bYOfxzw+NpcHjDON

jETpOQklVjP/WZslZ/1u2lq4/smCfu/DzQc9N3a17Y69nZ/vbN9e+YVlIAiCIAiCIAiCIP855LH9

AHsndLW+Zl1bvdtS754xulGir5C5zyGyKHS4urTZ6Rwpntopyft8fonoSono0TJZdA/43AOHJTcp

HpekPnf2jpuOLdOx92RR6j8S9B1kYz6vmz1gkI59pGOV8SVlla2GPUWpFp/SNb0Y2ljf2esugEqs

VqvpytonHykoVddzmFs9r79i/UciKVyuFpS1ItsG0d/oSxWJismcUhW4eL6UL1MFHdlPR16yfVe8

tPfvjh1BEARBEARBEARB/ir+hDrtT+eTSZ538yjMjoIwIwp72h3OBfpm3UNrvbR9/VKrvWOCoU7x

oS3cwe6qI+Hwac+hyEi0zxMMyP1yAEDOTeS0rBYfAzmd0VT5djovT2UzU2pWu9tQGstPJhO+yQTI

mjqjgZzNJOJaHGR1IjaejadUkG9lUik1rf3xPttocwC7Bzeo38cbecCid1ryvRZ//TsAI/da9HZL

HgTj7n3zbn/zewcjrFv0giU/wWvm/PXvHoyw4wf+QYtf5H6R+49Z9Nb9X+R+6zkNc3/XFvM3xhb4

nmvcP7qF3+QbUEsBAh4DFAAAAAgAgW5wUk9GY2qvAgAAqCIAAAUAGAAAAAAAAAAAAO2BAAAAAGlu

dHJvVVQFAANRHVBgdXgLAAEE6AMAAAToAwAAUEsFBgAAAAABAAEASwAAAO4CAAAAAA==This is obviously base64, so we run decode on it.

$ base64 --decode file.bin > decoded1

Running file on decoded1, we see that it is a zip file

$ file hello.txt

decoded1: Zip archive data, at least v2.0 to extract, compression method=deflate

Unzipping it, we get

$ unzip decoded1

Archive: decoded1

inflating: intro

Reverse Engineering

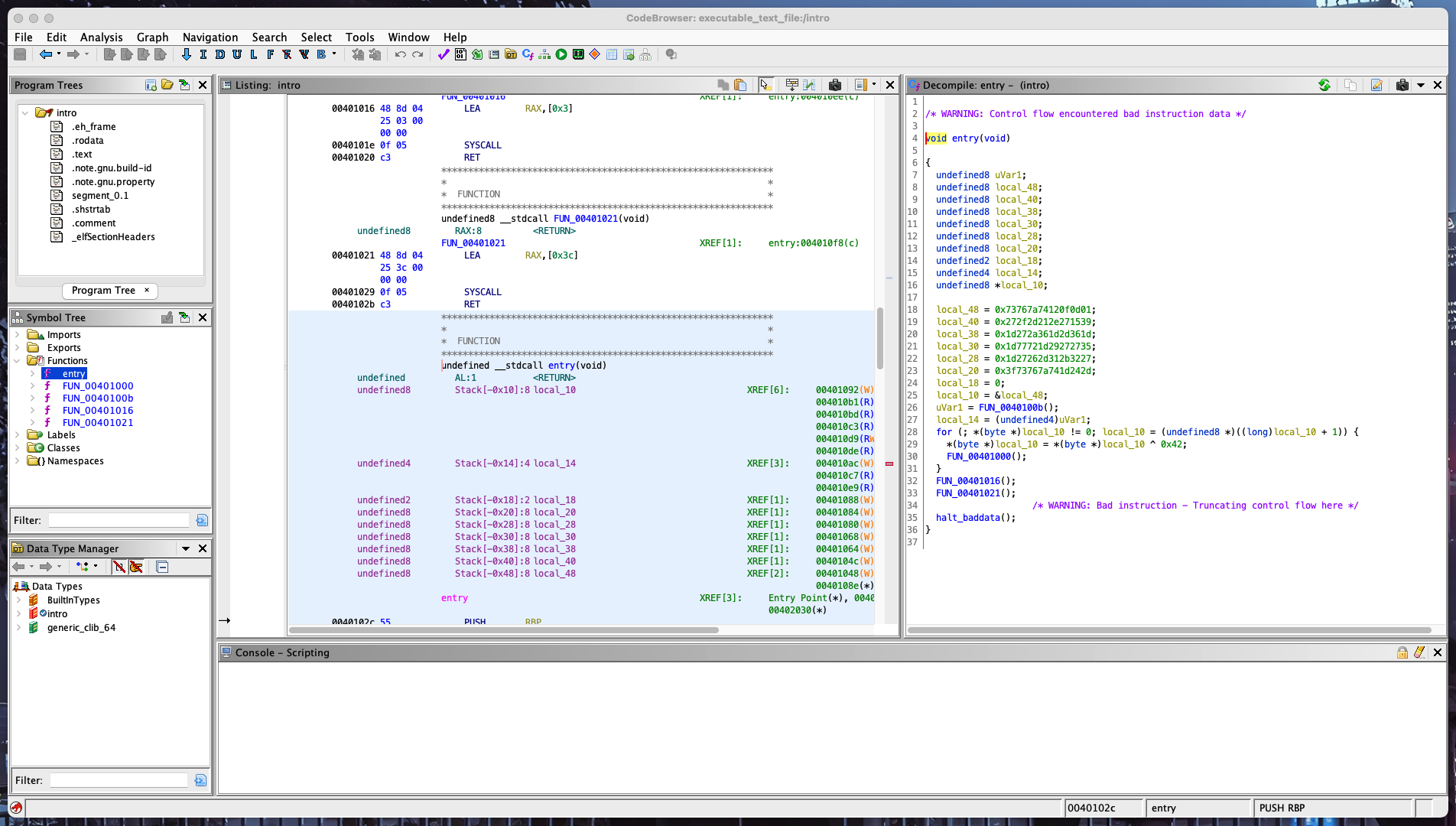

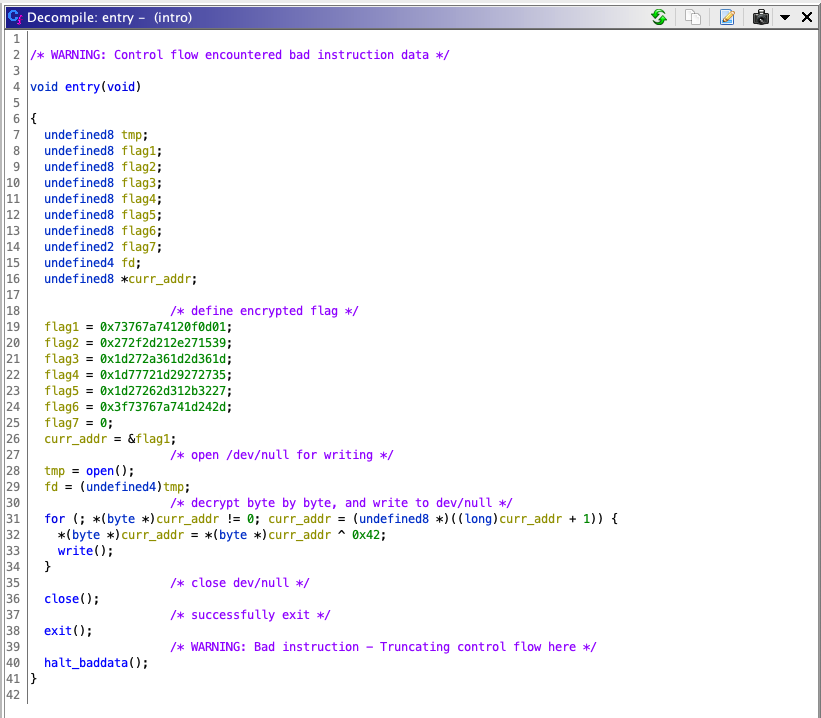

Unfortunately, running it doesn’t seem to do anything. It’s not giving any error messages, so it’s probably just running silently under the hood. To get some more information, we can put it into Ghidra and see what’s happening. After decompiling, this is what we see:

Note: Right click and hit “Open Image in New Tab” if you can’t make out the details of text

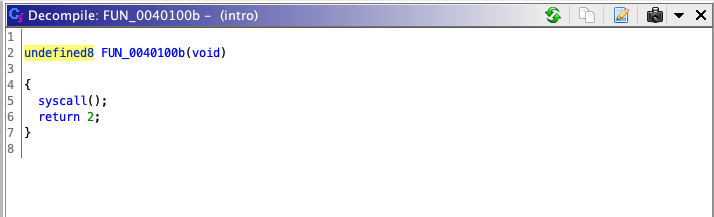

On the right, we seem to have alot of function calls (e.g. FUN_0040100b) which all just lead to a lone syscall with seemingly no arguments.

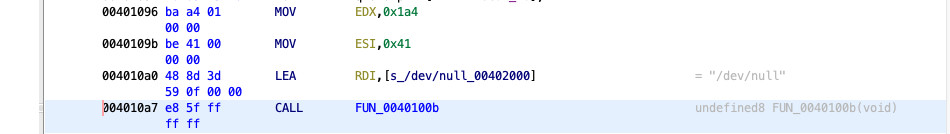

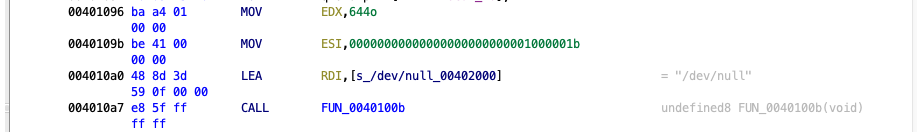

However, it’s important to note that just because Ghidra did not detect arguments when decompiling does not mean that they don’t exist. In these situations, it’s important to check the relevant assembly code out too. In particular, for this function, we see the following:

Here LEA (load effective address) is used to load the address containing the string "/dev/null" into RDI. Reading [OS Dev - Calling Conventions], we see that RDI is one of the parameter registers for \(x84_64\) architectures. In other words, this is an argument for FUN_0040100b. Looking at the other arguments and using some preexisting knowledge of C, it’s reasonable to guess that this is an open function call. Here is the same assembly, with each of the numbers converted into their correct types.

I.e. open("/dev/null", O_WRONLY|O_CREAT, 0644), which opens the file "/dev/null" for reading and writing.

Reading through the rest of the code, it seems that local_48, local_40, … local_18 form an null terminated string, and local_14 is being used to loop through the addresses of the string byte by byte. At each byte, we do XOR with 0x42 to obtain a new byte, and then call FUN__00401000()

Given that we opened "/dev/null" earlier, it is not a unreasonable assumption to assume that FUN__00401000() is writing the decrypted byte to "/dev/null". If we wanted to be sure, we could of course read the assembler code in more detail, but for now this educated guess is good enough.

Since manually checking the assembler code can be time consuming, it’s often better to use other methods if we can. Since we know that we are using a series of write() calls, we can use strace in order to grab all the system calls intro makes in it’s run time. Using strace gives:

$ strace ./intro

execve("./intro", ["./intro"], 0x7ffe6cf19f80 /* 26 vars */) = 0

open("/dev/null", O_WRONLY|O_CREAT, 0644) = 3

write(3, "C", 1) = 1

write(3, "O", 1) = 1

write(3, "M", 1) = 1

write(3, "P", 1) = 1

write(3, "6", 1) = 1

write(3, "8", 1) = 1

write(3, "4", 1) = 1

write(3, "1", 1) = 1

write(3, "{", 1) = 1

write(3, "R", 1) = 1

write(3, "E", 1) = 1

write(3, "D", 1) = 1

write(3, "A", 1) = 1

write(3, "C", 1) = 1

write(3, "T", 1) = 1

write(3, "E", 1) = 1

write(3, "D", 1) = 1

write(3, "}", 1) = 1

close(3) = 0

exit(0) = ?

+++ exited with 0 +++

Here, we can see the flag being written out byte by byte. Just for fun, let’s try and do some labelling and commenting back into the original Ghidra decompilation to make it a bit clearer.

Note: This is a rough guideline and once again, should not be interpreted as literal c code. For example, the arguments for all functions are still missing, and it is unlikely that the original code defined the flag as 8 variables.